- Desire Paths

- Posts

- The Practice of Everyday Tech

The Practice of Everyday Tech

How we shape technology in a technological age.

Mark Twain, in an 1880 Atlantic article, described that “queerest of queer things in this world – a one-sided conversation.” A byproduct of the first telephones, one not considered nor intended, was the ability of members of his household to annoy Mr. Twain by speaking loudly into a wooden box in the foyer. And they always yammered right when he was “writing a deep article on a sublime philosophical subject.”

Before 1880, anyone having a one-sided conversation was somewhere on the eccentric to insane continuum.

Now, of course, our public spaces are filled with uncouth creatures, earbuds nearly invisible, speaking at volume about whatever it is that those people need to speak of. They do this in, say, the grocery store or hospital-blood-draw waiting room.

(The latter oddly specific example happens to be true.)

Try fitting THIS into your ear. (A three-boxer circa 1880.)

I had the same queer sense Twain had when I moved back to the US in 2008 after spending a decade on a small island in Micronesia. I careened down the grocery aisle, overwhelmed by the endless corridors of cereal. I heard oblivious shoppers having one-sided conversations as I stood dumbfounded by the number and types of peanut butter available. I assumed these conversations were directed at me. I had never experienced a person speaking on a “cellular phone” while in a grocery store.

When I passed by these newfangled creatures, I bowed slightly, smiled, asked them what they wanted.

They looked at me like I was crazy!

According to Twain, “the gentle sex always shrinks from calling up the central office themselves.” Twain’s household duty was to make the switchboard connection for the ladies and then hand the horn to them. In fact, his phone was so new in 1880, that he just had to ask for “Mrs. Bagley” from the operator.

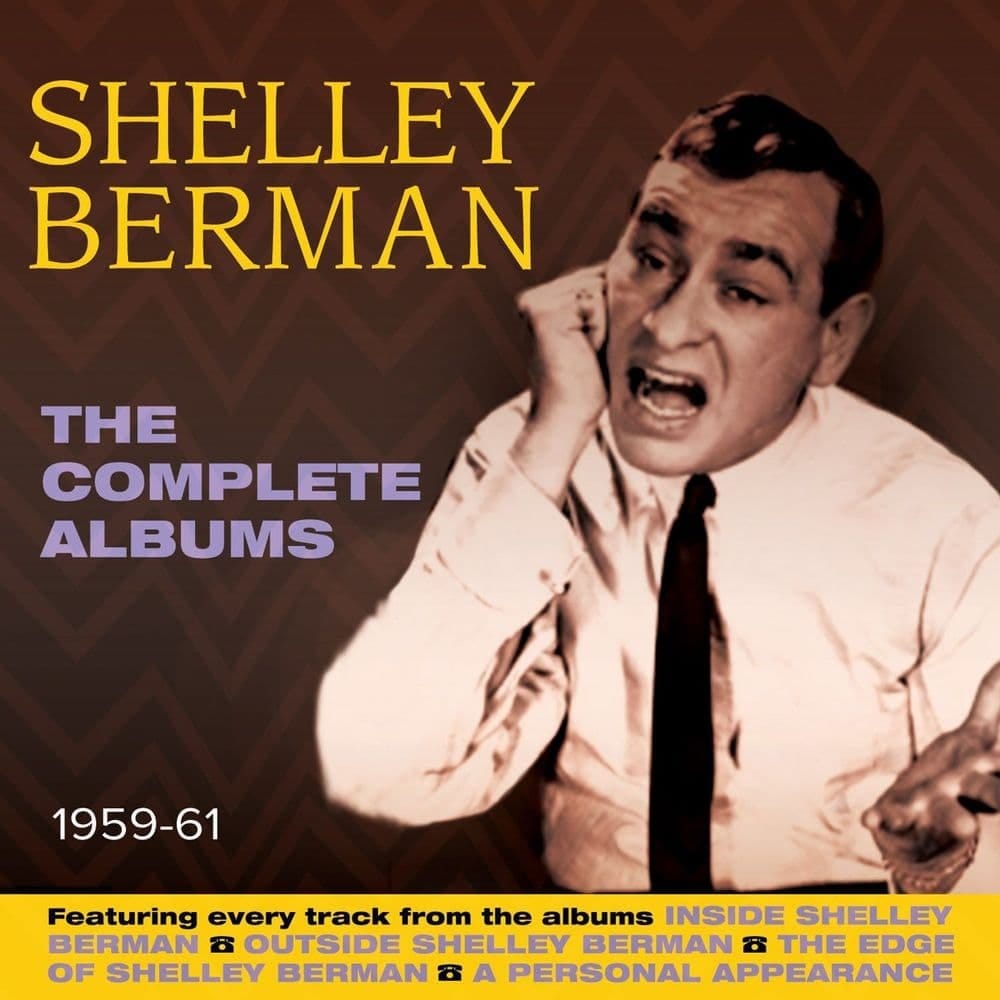

What ensues in Twain’s short article is the first “one-sided telephone gag”, a format that Shelly Berman and Bob Newhart perfected in the mid-twentieth century. (Berman thought Newhart stole the bit from him, but maybe they both got it from Twain?)

Did Bell Telephone produce their talking devices just so Twain, Berman, and Newhart could do comedy routines?

When you called someone on the aforementioned small island, Pohnpei, circa 2000 or so, you (the caller) would ask “Who is this?” This seemed a very queer practice until I understood what the caller was really saying was: “Am I allowed to talk to you?” If the person who answered your call was higher-ranking within the traditional clan or, say, the father of the girl you wanted to talk to, then you would immediately hang up. This is why fathers never answered the phone.

If you wanted to talk to a possible romantic partner on the phone, you had to find someone who was allowed to call the family. Maybe an aunt or uncle. And, as with Twain, they would make the initial connection and hand the phone to you.

I once spent one memorable, excruciatingly long evening talking to a woman’s father in his kitchen. Though the question would take but a minute, the preamble was somewhere between an hour and eternity. If I had a question to ask of an older respected person, it would be offensive simply to ask it. Instead, we drank potent kava, called sakau. The sakau process takes awhile. (It’s a whole thing). The father was bemused as to what I was doing in his house. Finally, when we were both relaxed into a relative stupor by the sakau, I told him the reason for my visit. Would it be OK if I called his daughter on the phone?

Not to be proud or kahla as they say on Pohnpei, but I spent the evening speaking with this fellow in a second language, Pohnpeian. I was more successful linguistically than romantically.

I did get telephone privileges. This saved a lot of hassle with “Lily’s” aunt and uncle. Now I could call direct and see if Lily wanted to drive around in my sports car while she hid below the dashboard on the passenger’s side floormat (so no one would see her). And maybe we could take the air at the coral dredging site? Nobody bothers you at the coral dredging site, with the moon shining bright upon the tinted windows of your car. The stone gray maze of dredging lanes beside the calm, reef-bound ocean. Your sweetheart slowly rising from her hiding place under the glove compartment.

All this was sort of exciting, in its way. However, I was being played – the lady in question used my public, father-approved phone calls as a cover for her actual goal, which was to have an illicit affair with a married man.

How could she be having an affair when this foreigner was calling her all the time?

Good for her! Way to use the telephone to your advantage.

The ladies of the Pwudoi clan react to my sick dance moves. (Pohnpei around 2006.)

Telephones weren’t invented to annoy Mark Twain. Or to provide comedy routines for Bob Newhart. Or facilitate extra-marital affairs on Micronesian islands.

And yet, humans bent this technology to their desire. They created the culture around technology by doing their daily activities. Joking. Dating. People are what Michel De Certeau calls “poets of their own acts.” They are “silent discoverers of their own paths” through the technological jungle.

In this way, Mark Twain and me and Lily and you are co-producers of technology. Technology is a made thing. What we do with it is up to us. We co-create technology with daily actions. As much as it may seem that technology is an unstoppable force, tech’s only meaning is in its use.

All of the instant messaging, A.I. summaries, or smart devices in the world won’t save you from at least one awkward conversation with someone’s dad. That’s life.

The thicker the sakau, the better the buzz.

Desire Paths seeps into your subconscious every two-weeks via your e-mail. Thursdays at 9AM. This is Desire Paths issue #15 (12 regular installments and three extras since 1/1/25) — check your Spam folder for past posts or just go to https://desire-paths-a4c079.beehiiv.com/ to see them all.

Reply